STUDENTS WITH DISABILITIES AND WIDENING PARTICIPATION GARY TAYLOR LIAM

GUIDELINES FOR WORKPLACE INSURANCE FOR POSTSECONDARY STUDENTS OFPHD STUDENTSHIP RESPONSIBLE RESEARCH AND INNOVATION CENTRE

PHD STUDENTSHIP – ARCHITECTURAL HERITAGE FACULTY OF

POLICY ON SITE SUPERVISION OF STUDENTS RATIONALE ADEQUATE

UNIVERSITY OF WARWICK STUDENTS’ UNION EQUAL OPPORTUNITIES

1 STUDENTS NAME DISCIPLINE INSTITUTECOUNTRY 1 (1) MR ALONGKOT

People without disabilities are more than 40 per cent more likely to enter higher education as those with disabilities (NAO, 2

Students with disabilities and widening participation

Gary Taylor, Liam Mellor and Lizzie Walton

There are numerous problems facing students with disabilities, both in terms of gaining access to higher education and accessing the support they need to navigate their way through their degree. People without disabilities are more than 40 per cent more likely to enter higher education as those with disabilities (NAO, 2002, p. 7). The problem of under-representation of people with disabilities is not necessarily the result of prejudice on the part of higher education institutes. Indeed, it has been found that higher education institutes welcome applications from students with disabilities (NAO, 2002). The problem appears to be located at an earlier stage in the education system. When addressing these issues, therefore, it is important to recognise that widening participation initiatives need to work towards forging links with pre-university educational provision and illustrate in a practical way that universities are open to all sections of the community. This may well require working with colleagues in the university sector to raise awareness of disability issues.

The problem

There are clearly many forms of disability and long-term illness that can create barriers to effective participation in higher education. Although mobility problems might be the most visible, there are other conditions that can have a serious impact upon the lives of students. It has been noted that approximately one third of university students in Britain suffer from poor mental health at some point during their studies. This poor health ranges from temporary periods of anxiety or depression to clinical disorders. University counsellors have reported that there is an increase in the number of students suffering from serious mental health problems like schizophrenia and manic depression. At a conference on student mental health in 2003, Rachel Tooth talked about her experiences as a student at Cardiff University and the impact they had upon her own mental health. She argued that students with mental health problems required a dedicated system of student support and that staff needed to be made aware of mental health issues (Buxton, 2002, p. 10).

Learning difficulties such as dyslexia and difficulties with hearing can also create significant obstacles for students. Universities are increasingly able to make provision for dyslexic students and attempts have been made to increase awareness of the condition and what can be done to help dyslexic students through their degrees. HEFCE’s ‘AchieveAbility’ project, for example, employs students with learning difficulties as outreach workers. These students go into schools and colleges to talk about education and the challenges they face. Workshops have been set up to provide information about learning, financial support, choosing courses and admissions procedures (Hewlett, 2005). Universities have also taken steps to make provision for the recruitment and education of students with hearing difficulties. For example, the University of Wolverhampton and the University of Central Lancashire provide a year 0 for students with hearing difficulties and have established a number of support mechanisms throughout their degrees. This support includes establishing career paths with potential employers and help with translation from British sign language to English (HEFCE, 2001). Such initiatives illustrate the importance of working with and adapting to the needs of disabled people with disabilities.

The composition of higher education institutes has changed considerably over the last two decades, as shown by the growth of an increasingly diverse student population. The numbers of students with disabilities has also grown. However, it was not until the 2001 amendment to the Disability Discrimination Act that it became unlawful to discriminate against disabled students. The amendment made it necessary for universities to anticipate the needs of disabled people rather than simply respond to their needs once they had arrived. According to Jacklin and Robinson (2007), the amendment has had a ‘significant impact’ on higher education in terms of the planning required to ensure compliance, as well as greater emphasis on how it is possible to ensure that the needs of students are met. These developments have taken place in tandem with the government’s widening participation initiatives and it has been argued that '... concerns about the most effective ways of supporting students with additional learning needs have become more prominent’ (Jacklin and Robinson, 2007, p.115). According to HEFCE, this legislation encouraged universities to provide an ‘… inclusive learning environment for students with disabilities’ (HEFCE, 2001, p. 5). With these changes in the law, universities have been required to think freshly about the ways in which they offer support to students with disabilities.

Universities have been quite creative in their responses to the changing legal rights of disabled students. The University of Nottingham, for example, set up a network comprising ten universities to share information about the needs of disabled students and to develop suitable policies. The aim was to generate and embed good practice in supporting students with disabilities (HEFCE, 2001). In terms of the facilities available for disabled students, The University of Nottingham provides a study support centre for one-to-one help, specialist facilities for blind students and those with impaired hearing, wheelchair access to halls of residence and a minibus on campus for those with mobility problems. All disabled students can apply for a Disabled Students’ Allowance, which provides a one-off grant for purchasing specialist equipment and services (Berliner, 2002). HEFCE (2001) noted that the University of Oxford had started to develop a system of extra support for students with disabilities and HEFCE argued that all universities should provide prospective disabled students with clear information about the facilities and support they can expect at university (HEFCE, 2001). All of this, however, works upon the assumption that students with disabilities have found a way into universities. The under-representation of disabled students has already been noted and it is clear that there are numerous barriers to disabled students participating in higher education. So what can be done about this?

The transition between FE and HE

If the problem of the under-representation of disabled students in higher education is to be addressed, it might be that universities need to look towards smoothing the transition into higher education from schools and from the further education sector. Sanderson (2001) argues, on the basis of research conducted at the University of Nottingham, that support for disabled students is particularly lacking in the transition between the further and higher education sectors. This study was based on interviews with:

Disabled students from further education colleges in Nottingham

Disabled students from the University of Nottingham

Tutors from the further education sector who are involved in supporting students with disabilities

All three groups felt there was a lack of information for disabled students. In particular, students and staff in further education colleges were concerned about the level of information available on such maters as assessment and option choices. It was ‘strongly’ felt that this information should be available before students attend university so that they can make an informed choice between institutions according to their individual needs. In a similar way, it was felt that universities should make it clear to disabled students what they intended to do with personal information disclosed on application forms. Many students feared that it might have an adverse effect upon their application. Moreover, staff in the further education sector felt that more information was needed on the Disabled Students Allowance. Sanderson found that most of the students involved in the study had no knowledge of the allowance (Sanderson, 2001, p. 230).

This problem of inadequate information has been noted by a number of authors. Many disabled students have had problems accessing information about courses. According to Holloway (2001), disabled students could be helped by the provision of funds for individual learning support. All of the students in the study were forced to pay out more money to assess course information because of their disability. Although funding was predominantly met by a combination of the Disabled Students’ Allowance and parental support; where this was not sufficient in covering the students’ needs, additional funding had to found or, conversely, students had to ‘do without’ (Holloway, 2001, p.600). In research conducted by Fuller, Bradley and Healey (2004) it was noted how students with disabilities had some concerns about the information provided during and after the application process. A ‘small number’ of students felt that their decision about which university to attend was hampered by an inability to get information about what was offered for disabled students in terms of their learning and assessment needs. Such information was only provided once a place had been offered. Moreover, once at university students with disabilities noted that tutors were not informed of their conditions, despite having given this information to the university. This could subsequently cause problems in communication (Fuller, Bradley and Healey, 2004, p. 465). Without sufficient information, many disabled students find that they are making their choices in the hope (rather than in the knowledge) that support mechanisms will be in place.

Sanderson (2001) has noted how students with disabilities have talked about the importance of having access to essential services. Here, the research identifies three key factors. Firstly, the availability of networked computers is seen as a crucial component of higher education. All of the respondents in Sanderson’s study indicated that they would not choose a university unless it had access to these facilities. It was argued that computers should be located near to study areas and available 7 days a week. Secondly, one-to-one learning support for disabled students was said to be especially important to students still in further education but less so for students in higher education. Dyslexic students in particular felt that this type of support was crucial. Thirdly, staff in further education colleges identified the need for interpreters to work alongside students with hearing difficulties. Students with such difficulties were often unsure about applying for a place in university because of uncertainty over the provision of support workers who could use sign language. Two visually impaired students also stressed the need for information to be provided in Braille (Sanderson, 2001, p. 231-232).

Students with disabilities have argued that it is important to have a named person to deal with, especially in the transition between further and higher education. For students in further education the role involved having someone at universities who could answer questions without the department of their choice. Staff in further education concurred that a ‘named person’ to assist in applications. Students in higher education identified a more specific role for the ‘named person’, who would ideally be located within the department and have in-depth knowledge of the subject. Staff in higher education proposed a mentoring system for disabled students in order to reduce the loneliness and/ or isolation that many disabled students are said to feel at university and which accounts for a large amount of students who dropout or fail in higher education. (Sanderson, 2001, pp. 232-233).

The research conducted by Sanderson revealed that a great deal could be done to assist disabled students in their applications to university. In particular, Sanderson emphasised the following:

Universities need to provide detail about the provision they make for disabled students

The further education sector needs to help disabled students by finding out what is available at university level

There needs to be clear communication between further and higher education on the needs of disabled students

Universities need to listen to what disabled students say they require and provide information about such provision when they require it

Universities need to enhance their current provision in line with stated requirements.

Only through better communication between the two educational sectors regarding the needs of disabled students will such students be encouraged to enter higher education.

Problems facing students with disabilities

Once at university, students with disabilities often face numerous difficulties. Research conducted by Fuller, Bradley and Healey (2004) showed that students with disabilities often find taking notes more difficult than students without disabilities. For some students, difficulties arose from lecturers talking too quickly; talking whilst not facing the class; and removing visual material too quickly. Some students with disabilities also experienced difficulty in taking notes while listening and watching. This often resulted in the production of poor quality notes. Yet, the use of pre-pared notes could also prove just as difficult (due to font-size, single-spacing). Disabled students also found participation in group discussions rather difficult. This might have been because of the ability to hear and/ or see the lecturer or other students, as well as the pace of discussion. However, students were also asked to reflect upon the good practices that had helped their learning experience. One student noted that the use of a Dictaphone made lectures far less daunting (Fuller, Bradley and Healey, 2004, p. 462).

The way that universities organise assessments for their courses can also create problems for students with disabilities. Evidence from interviews indicates that a number of disabled students experience difficulty with written coursework, exams and oral presentations. Spelling and grammar, anxiety, exhaustion associated with the extra time needed to complete work and the lack of clear guidelines can be disempowering to disabled students. Assessment criteria can thus influence some students’ choice of course and modules. Areas of good practice were also highlighted. One student spoke of the variation in the assessment criteria, which involved a positive combination of a skills test, exams and a portfolio (Fuller, Bradley and Healey, 2004, pp. 463-4). Methods of assessment are likely to influence the majority of students, not only those with disabilities. It should be recognised, however, that students with disabilities encounter more obstacles than the majority of students and that we should be mindful of this when designing assessment packages for the modules we teach.

An area of concern identified by all students interviewed by Holloway (2001) was the effort and time required to organise their own support. Students found that they had to voice their needs on numerous occasions, such as during exam periods or to gain access to buildings. The students’ quality of experience also depended upon the level of provision made by the university and upon positive responses from staff. However, in most cases students were expected to play an active role in organising their own support. This led to difficulties in getting reliable information and having to find ways to make ‘the system’ work. The added time and stress was seen as part of being a disabled student. Accessing information from the library rated highly in terms of the time and stress involved. Students found that they were constantly expected to explain their needs when they used the library because there is often no common policy or practice in place. Similarly, exam arrangements (such as the allocation of extra time) differed between departments, again adding to stress levels. Disabled students were also reliant on helpers to provide support. Planning work around the availability of such help can also cause extra stress. Staff were said to be supportive overall, although responses ranged from good to bad. Students responded positively to well-informed staff, but they were rather less happy about members of staff who lacked knowledge or awareness on the problems faced by students with disabilities (Holloway, 2001).

Student views on support needs

It is clear that students with disabilities encounter a number of obstacles to the successful completion of their work and that they have a range of support needs. These needs will of course differ depending upon the student, but they often include access to specialised equipment or facilities. It has been noted that assistance required by students with disabilities often includes funding or equipment; scanners and computers with voice synthesisers in libraries, flexible systems in the library, information networks, disabled parking and access and exam arrangements which take into account the needs of disabled students (Holloway, 2001). These resources can help students with disabilities to attend university and access facilities in a more flexible way. This is often important for students who have difficulties with some of the tight deadlines imposed by universities and whose health is adversely affected by their disability.

Access to equipment and material resources, however, needs to be accompanied by some level of pastoral support. Research conducted by Jacklin and Robinson (2007) revealed that students with disabilities value a range of support including somebody to talk to about programme expectations or workload, a listening ear when feeling stressed about workload or about personal matters, reassurance that they are capable of doing the work, help with essay writing and financial advice. Personal and interpersonal support was seen as crucial. Encouragement was deemed particularly useful, especially if it provided opportunities to talk to other students about work (Jacklin and Robinson, 2007, p. 116-118). Support can be provided by a variety of people. Other students can be particularly important. This does not absolve universities, however, for taking some responsibility for providing pastoral support for students with disabilities.

In addition to having the support of specialists in disability, students also require the support of their lecturing staff. Students with disabilities have been particularly critical of a general lack of awareness amongst lecturing staff. These students often require copies of handouts and lecture slides/powerpoints. They also need to know that they will not be disadvantaged by the assessment methods used and by the timetable for completing assignments. Holloway (2001) noted how there was a general lack of common policies to deal with the needs of students with disabilities and that this led to a system of ad hoc and inconsistent responses by members of the teaching staff. Sanderson (2001) argued that lecturers need to be educated into the needs of disabled students, perhaps through the introduction of a compulsory course for lecturers on disability issues. These authors recognise that students with disabilities are not only disabled by their particular condition but also by the environment and by the lack of awareness of those around them. This is something that can be rectified.

Conclusion

The literature shows that if universities want to attract students with disabilities, something needs to be done to improve communication and to ensure that the needs of disabled students are met on a number of different levels. In particular, it has been argued that attempts should be made to work closely with the further education sector to create a conduit for students with special needs and thereby reduce some of the frustrations experienced by many disabled students when trying to access reliable information about coursers and about the levels of support they can expect. It has also been noted that universities need to be flexible in their dealing with disabled students and to find ways to minimise the obstacles to disabled students participating fully in the life of the university. This requires not only formal processes, but also the willingness of staff to take into account the needs of different sections of the student community.

Bibliography

Berliner, W. (2002) ‘Clearing 2002: In the mix’, The Guardian, 15 August 2002, p. 16.

Buxton, A. (2003) ‘The saddest university challenge of all: Mental illness tests students and colleges’, The Daily Telegraph, 12 April 2003, p. 10

Clarke, C (2003) The future of higher education, London: The Stationary Office.

Fuller, M., Bradley, and Healey, M. (2004) ‘Incorporating disabled students within an inclusive higher education environment’, Disability and Society, Volume 19, pp. 455-468.

HEFCE (2001) Strategies for learning and teaching in higher education

Hewlett, K. (2005) ‘The Art of Demolishing Barriers’, The Times Higher Education Supplement, 4 March 2005, p. 58

Jacklin, A. and Robinson, C (2007) ‘What is meant by support in higher education? Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs, Volume 7, pp. 114-123.

Holloway, S. (2001) 'The Experience of Higher Education from the Perspective of Disabled Students', Disability and Society, Vol. 16, No. 4, pp. 597-615.

Konur, O. (2000) 'Creating Enforceable Civil Rights for Disabled Students in Higher Education: an institutional theory perspective', Disability and Society, Vol. 15, No. 7, pp. 1041- 1063

Low, J. (1996) 'Negotiating Identities, Negotiating Environments: an interpretation of the experiences of students with disabilities', Disability and Society, Vol. 11, No. 2, pp. 235-248

National Audit Office (2002) Widening Participation in Higher Education in England, London: The Stationary Office.

Sanderson, A. (2001) ‘Disabled Students in Transition’, Journal of Further and Higher Education, Volume 25, No. 2, pp. 228-240.

1 STUDENTS WHO WILL BE JUNIORS AND SENIORS IN

14 EXPLORING SECONDARY STUDENTS’ USE OF A WEBBASED 20

16 JAN 2019 MEMORANDUM FOR STUDENTS ENROLLED IN CMGT

Tags: disabilities and, with disabilities, widening, students, taylor, participation, disabilities

- POWERPLUSWATERMARKOBJECT357831064 CAPSTONE SCIENCE UNIT 6 HUMAN ACTIVITY & ENERGY

- SENIOR PHASE LEARNING PROGRAMME THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN MEMORY AND

- FURTHER EDUCATION FUND COURSES COVERED AND NOT COVERED BY

- ECCE LIBRIS JÍZDA SPECIÁLNÍHO VLAKU KNIHOVNICKÉHO A SPISOVATELSKÉHO DNE

- MUNICIPIO DE HACARÍ NOMBRE COMPLETO HACARÍ FUNDACIÓN AGOSTO 2

- REFLEXIONES Y PROPUESTAS SOBRE LA POLÍTICA FARMACÉUTICA FEDERACIÓN DE

- 27 ABSTRAK EVALUASI PENETAPAN HARGA POKOK PRODUKSI CRABMEAT (STUDI

- Mss16309 Mssjeva Nagrada za Diplomska Dela s Področja Mladih

- DIGITALTV OG INTERNETT FRA CANAL DIGITAL TIL BEBOERNE BAKGRUNN

- FÍSICA Y QUÍMICA – 4º ESO – EVEREST PRIMER

- SECUENCIA PASO A PASO DE LA INSTALACIÓN DE XERXESMETALIB

- GROUP 6 PROMOCIÓN DE LA COOPERACIÓN E INTEGRACIÓN DEL

- 3 TRICKS TO AVOID MISSING FONT STYLES IN POWERPOINT

- SUNSHINE CORNERS A NONPROFIT CHILD CARE CENTER CARING FOR

- CTX ‘TELL A FRIEND’ CONTENT A SHORT EXPLANATION OF

- PÉCSI TUDOMÁNYEGYETEM ÁLTALÁNOS ORVOSTUDOMÁNYI KAR TANULMÁNYI HIVATAL VIZSGAIDŐPONT BEJELENTŐ

- FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS PPI PROGRAM ELIGIBILITY HOW DID YOU

- IV THERAPY – CENTRAL VENOUS CATHETERS COURSE (INCLUDES CV

- REFERAT FRÅ OPPSTARTSMØTE PROSJEKT MØTEREFERAT VEDK REGULERINGSPLANARBEID FOR GNR

- SENATE NO 2909 STATE OF NEW JERSEY 215TH LEGISLATURE

- AUSTRALIAN GOVERNMENT REGULATION IMPACT STATEMENT STATUS BY AGENCY

- STANDARD FORM CONTRACT DOCUMENTS – MINI MINOR WORKS SAMPLE

- ORDEN DE XX DE JULIO DE 2012 DE LA

- 2019 FRIENDS OF THE POOR® WALK FORMA DE REGISTRO

- HS (MA) „HOCHSCHULGESPRÄCHE“ – WS 2009 (BOETTCHER) LITERATURHINWEISE ZUM

- EL PRIMER MANDAMIENTO PON A DIOS EN PRIMER

- CONTRATO DE PRESTAÇÃO DE SERVIÇOS PROFISSIONAIS PELO PRESENTE INSTRUMENTO

- 94246 Guidance Note on the Development and Implementation of

- 1 KALENDAR JE POPIS SVIH DANA I

- CASE STUDY ECOTOURISM SARAWAK MALAYSIA TOURISM IS THE FASTEST

GRUNDSCHULDIDAKTIK BLOCKPRAKTIKA (FACHDIDAKTISCHES BLOCKPRAKTIKUM) VOR PRAKTIKUMSANTRITT SOLLEN FOLGENDE LEHRVERANSTALTUNGEN

ACTA DE LA CELEBRACIÓN DEL CONCURSO OFICIAL DE VINOS

ACTA DE LA CELEBRACIÓN DEL CONCURSO OFICIAL DE VINOSETABLISSEMENT SCOLAIRE OU ÉCOLE ADRESSE N° DE

KENTUCKY LEGISLATIVE ETHICS COMMISSION GEORGE TROUTMAN CHAIR PAT FREIBERT

KENTUCKY LEGISLATIVE ETHICS COMMISSION GEORGE TROUTMAN CHAIR PAT FREIBERT F ILMSKRIPT ZUR SENDUNG „PETER STAMM“ SENDEREIHE „AUTOREN ERZÄHLEN“

F ILMSKRIPT ZUR SENDUNG „PETER STAMM“ SENDEREIHE „AUTOREN ERZÄHLEN“ JEDINSTVENI UPRAVNI ODJEL KLASA11203150102 URBROJ218618031152 LUDBREG 26 OŽUJKA 2015

JEDINSTVENI UPRAVNI ODJEL KLASA11203150102 URBROJ218618031152 LUDBREG 26 OŽUJKA 2015ASSIGNMENT FOR WEEK 08 JULIA KRIPKE MARK MELAHN AND

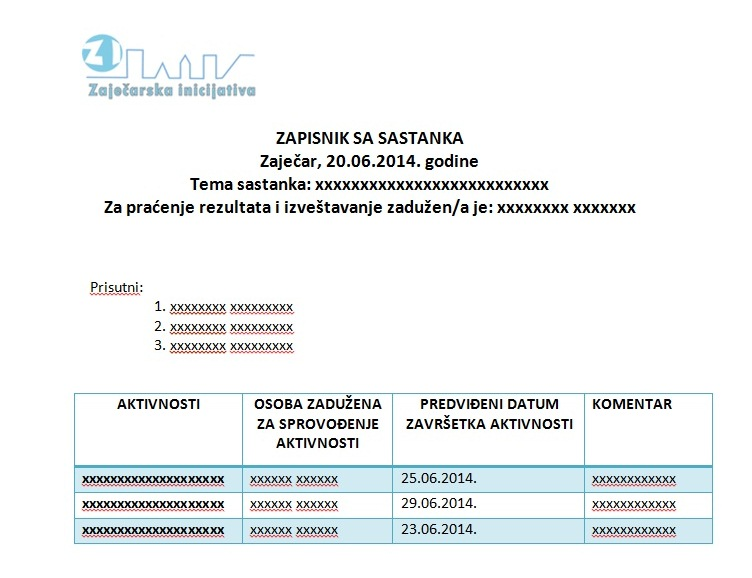

KULTURA POSLOVNE KOMUNIKACIJE UNAPREĐENJE I STANDARDIZACIJA KOMUNIKACIJE SA CILJNIM

KULTURA POSLOVNE KOMUNIKACIJE UNAPREĐENJE I STANDARDIZACIJA KOMUNIKACIJE SA CILJNIMNOK SAMTALER – MEN IKKE COACHINGSAMTALER! AF SEKRETARIATSLEDER HENRIK

………………………………………………………………………………………… I JORNADAS DOCTORALES DE CASTILLA LA MANCHA REPUTACIÓN

………………………………………………………………………………………… I JORNADAS DOCTORALES DE CASTILLA LA MANCHA REPUTACIÓNUSER TESTING II JEREMY HYLAND DISCUSSION QUESTIONS DISCUSSION STARTER

PHONE 00962 799416235 • EMAIL MJ11AHOTMAILCOM AMJAD NAJI ABUIRMEILEH

CUESTIONARIO SOBRE EL GOBIERNO Y LA DIRECCIÓN DE LA

CUESTIONARIO SOBRE EL GOBIERNO Y LA DIRECCIÓN DE LA EL ESTUDIO DEL ESPÍRITU SANTO LA PERSONALIDAD Y DEIDAD

EL ESTUDIO DEL ESPÍRITU SANTO LA PERSONALIDAD Y DEIDAD CEGLÉDI KÖZGAZDASÁGI ÉS INFORMATIKAI SZAKKÖZÉPISKOLA ISKOLAI RENDEZVÉNYEK SZERVEZÉSE CIIB02

CEGLÉDI KÖZGAZDASÁGI ÉS INFORMATIKAI SZAKKÖZÉPISKOLA ISKOLAI RENDEZVÉNYEK SZERVEZÉSE CIIB02INTERVIEW WITH KATHY BLACK [AT AMHI FOR 710 DAYS

L’OBRA CONSISTEIX EN CONNEXIÓ O ESTESA ELÈCTRICA AIGÜES

L’OBRA CONSISTEIX EN CONNEXIÓ O ESTESA ELÈCTRICA AIGÜESARBEIDSGRUPPE KULTURMINNEPLAN REFERAT MØTE 100118 STED MØTEROM 1 GRAND

AUGUST CALENDAR THIS CALENDAR TEMPLATE IS BLANK PRINTABLE AND

INTRODUCTION MOODY COUNTY HIGHWAY DEPARTMENT SNOWICE REMOVAL PROCEDURES