PARENTS AND PEERS INFLUENCES ON EMOTIONAL ADJUSTMENT DURING ADOLESCENCE1

10TH SEPTEMBER 2021 DEAR PARENTS AND CARERS MUSIC TUITION2015 BROWNELL TALBOT GRANDPARENTS DAY MUSIC PROGRAM MORAN RECORDING

202122 COLLEGE PLANNING FOR SENIORS AND THEIR PARENTS FALL

3 CONTINUING THE JOURNEY TRANSITION TIPS FOR PARENTS OF

30 HOURS EXTENDED ENTITLEMENT WORKING PARENTS OF 3 AND

A GUIDE FOR PARENTS SEEKING MENTAL HEALTH SERVICES FOR

Parents and peers influences on emotional adjustment during adolescence

Parents and peers influences on emotional adjustment during adolescence1

Oliva, A., Parra, A. y Sánchez-Queija, I.

University of Sevilla

Spain

Most of the studies about social relationships and adolescent adjustment focus on parents or peer group as separate sources of influence and do not take into account interaction effects. The aim of this paper is to study the influence of relationships with parents and peers on emotional adjustment in a sample of spanish adolescents. Participants in the study were 221 boys and 292 girls, aged between 13 and 19 years, that filled out instruments about family relationships (Parental Style; Family Adaptability and Cohesion; Conflicts and Comunication) peer attachment, self.esteem and life satisfaction. Results show that peer attachment and parental support and affection promote emotional adjustment of boys and girls, specially during middle adolescence. For older adolescents, peer relationships seem to be more important than parental support. Results did not reveal interaction effects, so parents and peers have an independent influence on emotional adjustment.

INTRODUCTION

Given the high incidence of emotional problems during adolescence, and the important consequences these problems can have for further social adaptation (Adams & Gullotta, 1989), it has a social and scientific interest to research the influences on emotional adjustment of adolescents.

Family relationships appear as an important source of influence on self-esteem and life satisfaction of boys and girls (Barber & Lyons, 1994; Conger, Conger & Scaramella, 1997; Helsen, Vollebergh y Meeus, 2000), but power of influence on emotional adjustment of peers increases dramatically during adolescence (Savin-Williams & Berndt, 1990; Degirmencioglu, Urber, Tolson & Richard, 1998). Anyway, despite their growing reliance on peers for support, most adolescents continue to rely on their parents for emotional support and advice.

An important focus of interest is has to do with how are the relationships with parents and peers related to each other, and how parental and peer support interact and moderate their effects on emotional adjustment of adolescents. According to Helsen et al. (2000), three alternative points of view can be found in the literature.

- Conflict or compensation hypothesis or model: Parental and peer support are negatively correlated, and peer attachment could compensate for the emotional problems of boys and girls with unfavourable relationships with their parents.

- Continuity or reinforcement model: From the perspective of the attachment theory (Bowlby, 1972), internal working models built on the basis of children’s relationship with their parents will have a significant influence on peer relationships. So attachment to parents and friends will be positively correlated. Also, it could be hypothetized that attachment to peer would have a more positive influence on emotional adjustment in the context of positive family relationships.

- Aditive model. From this point of view family and peers are independent social contexts (Berndt, 1979), and parental and peer support would not be correlated and would represent separate contributions to adolescent adjustment.

The aim of this research was to study the role of parents and peers in the emotional adjustment of a sample of spanish adolescents. First, we were interested in the validation of the hypothesis that parental support decreases while peer support increases along adolescence. Also, we expected to find gender differences, with girls showing a higher attachement to parents and friends than boys. With regard to the association between attachment to parents and peers we hypotethized a positive correlation: adolescents experiencing higher parental support will show a higher peer attachment (continuity model). We did not have a clear hypothesis about interaction or moderating effects of parent and peer on emotional adjustment, but the aditive model seems to us more plausible.

METHOD

Subjects

The sample used during the study consisted of a total of 513 adolescents (221 boys and 292 girls) aged between 13 and 19 (M=15.43, and SD=1.19), all attending private or state schools in Seville and its surrounding region. Subjects were selected from a total of 9 schools (5 in the capital, 3 in rural areas and 1 in the metropolitan area) chosen on the basis of population size and type (private or state institution). Within each school, an entire class was selected from each educational level. In schools with two or more classes per level, one class was selected at random.

Instruments

For the purposes of the study, a questionnaire was compiled which included a number of different instruments related to family relations, peer relations and various aspects of personal development. Some of these instruments were developed ad hoc for this study, while others were adaptations or translations from the works of other researchers.

Parental support

- Parental style was assessed using an instrument created by Lamborn et al. (1991), consisting of 24 items which explore the adolescent’s perception of the educational or disciplinary style used by his/her parents, classified according to two dimensions: acceptance or affection (= 0.71) and supervision (=0.70).

-FACES II (Family Adaptibility and Cohesion Scale: Olson, Portner and Lavec, 1985). With 30 items and two dimensions: cohesion (=0.75) and adaptability (=0.75).

- Communication with parents. Elaborated for this study, included 11 items assesing communication with the father and 11 items assessing communication with the mother.

- Conflict with parents. 14 items to assess parents-adolescent conflict.

Peer attachment

-Peer attachment. The study used an adaptation of a 24-item scale developed by Armsden and Greenberg (1987) for assessing factors such as trust (=0.83), communication (=0.81) and alienation (=0.72) in peer relationships. The scale has a reliability rating of =0.70.

Emotional adjustment.

-Self-esteem. We used a scale developed by Rosenberg (1973), consisting of 10 items that assess a subject’s general level of self-esteem. The scale has a reliability rating of =0.80.

-Life satisfaction. This variable was measured using a 5-item scale developed by the authors with a reliability rating of =0.80.

Procedure

Questionnaires were anonymous and applied by members of the research team. The objectives of the study were explained to the headmasters/headmistresses of the selected schools during initial written and telephone contacts, after which an interviewer visited the school and selected the necessary classes. The subjects from each selected class completed the questionnaire during two collective 45-minute sessions which took place on two different days.

RESULTS

A factorial analysis was performed with all the variables relatives to parents (affection, supervision, cohesion, adaptability, communication and conflict). Only one factor was extracted accounting for 50.2% of the variance. We used the label of Parental Support for this factor. As is shown in figure 1, there are some gender differences in the evolution of parental support through adolescence. So while parental support remain stable for girls from early to late adolescence (p=.919), among boys is observed a significant decrease (p=.000). All ages girls perceived a higher parental support than boys (p=.000).

Peer attachment experiences a slight increase from 13 to 15 years (p=.042 for girls, and p=.051 for boys), and girls show higher scores than boys (Figure 2).

Partial correlations between parental support and peer attachment (after controlling effect of age), are significant for boys (r=.311, p=.000) and girls (r=.27, p=.000), indicating a strong association between both variables. Those adolescents experiencing higher parental support establish more supportive relationships with peers (table I).

Self- esteem and life satisfaction were considered indices of emotional adjustment. Table II shows correlations between these indexes and parental support and peer attachment for early, medium and late adolescents. All correlations are positive and significant, so parent and peer attachment are similarly related to emotional adjustment: self-esteem and life satisfaction are higher among adolescents with better relationships with parents and peers. Anyway, is important to point out that, among late adolescents, influence of peers on adjustment is more powerful than influence of parents. Taking into account the strong association between self-esteem and life satisfaction ( r=.48 ), a new variable named emotional adjustment was created with the mean of these two variables.

As far as parental support and peer attachment are strongly associated it could be that only one of these variables were related to emotional adjustment, influencing the association between the other variable and emotional adjustment. So a multiple regression analysis was performed to look at the connections between the support of parents and peers and emotional adjustment. The variable emotional adjustment was the dependent variable and gender, age, parental support, peer attachment were the independent variables. To detect interaction effects, after standardising the predictive variables, a new independent variable was created by multiplying parental support by peer attachment and included as another independent variable following the procedure proposed by Aiken and West (1991).

As is shown in table 3, both parental support and peer attachment had a significant influence on emotional adjustment, and adolescents with more support from parents and peers showed a better emotional adjustment. Interaction effects were not detected, and the influence of peer atachment seems to be independent of grade of parental support and vice versa. Gender had a significant influence: boys were more adjusted than girls.

Finally we decided to create four groups of adolescents according to the levels of parental support (high versus low) and peer attachment (high versus low). Table 4 shows that boys and girls receiving a high support from parents and friends are the most adjusted.

DISCUSSION

Results of this study do not support conflict or compensation theory about parents and peers relationships. On the contrary, as could be predicted from a continuity or attachment theory point of view, we found a significant association between attachment to parents and peers. Anyway, even when this correlation is higher than correlations found in other studies (Helsen et al, 2000; Nada Raja et al, 1992), is not stronger enough to reject the point of view supported by Berndt (1979) that parents and peers represent relatively isolated social contexts.

Also, we did not find any interaction effect, and parents and peers have significant and independent influences on emotional adjustment, so our data give support to an aditive model of family and peer influences. Boys and girls with positive relationships to both peer and parents reported the best emotional adjustment, while those adolescents lacking in support from parents and peer showed the worst adjustment.

While the power of influence of parents and peers is quite similar in early and middle adolescence, during late adolescence a different picture appears, and self-esteem and life satisfaction seems to be more related to peer attachment. As some authors pointed out (Furman and Buhmester, 1992; Dekovic, 1999; Laible et al, 2000), adolescents begin to relay on peers more often than parents as sources of support, maybe because of many factors such as increasing autonomy from the family, or emerging new concerns and interests that they share with their friends.

As we hypothetized , results of the study shows a decrease in perceived parental support, but this is true only for boys. One likely explanation for these gender differences it has to do with the different socialization processes experienced for boys and girls in Spain that promote in boys a greater autonomy from the family, while girls are expected to maintain closer relationships with their parents during adolescence and adulthood. Gender differences are less important in peer attachment, that shows a significant increase, mainly from early to medium adolescence , although girls present higher scores than boys.

Figure 1. Parental support by age and gender

Figure 2. Peer attachment by age and gender

Table I. Partial correlations between parental support and peer attachment after considering the effects of age

-

Boys

r

Girls

r

.31**

.27**

**p<0,001, *p<0,01 +p<0,05

Table II. Correlations among parental support and peer attachment and emotional adjusment variables.

|

|

Parental support |

Peer attachment |

||||

|

|

12-14 r |

15-16 r |

17-19 r |

12-14 r |

15-16 r |

17-19 r |

|

Self-esteem |

.23+ |

.31** |

.18+ |

.25* |

.27** |

.24* |

|

Life satisfaction |

.29* |

.39** |

.17+ |

.33** |

.31** |

.39** |

**p<0,001, *p<0,01 +p<0,05

Tabla III. Variables predicting emotional adjustment

-

Emotional adjustment

Beta

R2

Change R2

1 Age

.00

.00

.00

Gender

.24**

2 Parental support

.23**

.16

.16

Peer attachment

.29**

3 Parental support x Peer attachment

.03

.16

.00

**p<0,001, *p<0,01 +p<0,05

Tabla IV. Scores in emotional adjustment according to parental support and peer attachment

-

Emotional

adjustment

High parental support and high peer attachment

26,14

High parental support and low peer attachment

24,14

Low parental support and high peer attachment

24,07

Low parental support and low peer attachment

22,82

1 Paper presented at VIII EARA Conference. Oxford, 2002.

A NOTE TO PARENTS A FRONTED ADVERBIAL IS A

A NXIETY MANAGEMENT FACTS & STRATEGIES FOR PARENTS 1

ACT COUNCIL OF PARENTS & CITIZENS ASSOCIATIONS RESPONSE

Tags: adjustment during, emotional adjustment, influences, parents, during, adolescence1, emotional, adjustment, peers

- KEPUTUSAN PRESIDEN REPUBLIK INDONESIA NOMOR 125 TAHUN 2001 TENTANG

- ATTRACTING INTERNATIONAL STUDENTS EQUITABLE SERVICES AND SUPPORT CAMPUS COHESION

- 27 O’ZBEKISTON RESPUBLIKASI OLIY VA O’RTA MAXSUS TA’LIM VAZIRLIGI

- MONITOREO DE LA IMAGEN DE LAS MUJERES INDÍGENAS EN

- DENİZYOLU İLE YAPILACAK DÜZENLİ SEFERLERE DAİR YÖNETMELİĞE İLİŞKİN UYGULAMA

- JANN MONTHLY BRIEFING NOVEMBER 2006 1 POLITICAL

- PER INFORMAZIONI GENERALI SUL MATRIMONIO CLICCA QUI HTTPWWWESTERIITMAEITITALIANINELMONDOSERVIZICONSOLARISTATOCIVILEMATRIMONIOHTM PER

- OUR SCHOOLS EUROPEAN CANADIAN AND MIDDLE EASTERN SCHOOLS BULGARIA

- INSTRUCCIONES Y PUNTUACIÓN CONTESTE A TODAS LAS PREGUNTAS DE

- BUESKYTTENS ORDBOG 1 ANKERPUNKT ER DET PUNKT SOM MAN

- EL GEN COMO UN NUEVO ICONO CULTURAL PATRICIA DIGILIO

- UNA EMISION EN DIRECTO DE RADIO MONTGRI Y… ¿CUÁNTO

- AL STERELEES WITHINNE A BOOT THE LAYERS OF FATE

- “THE PRINCIPLE OF GOOD FAITH IN THE LAW OF

- PERATURAN MENTERI HUKUM DAN HAK ASAI MANUSIA REPUBLIK INDONESIA

- (B TEKNOLOGI) PERBAIKAN PROSES PENGOLAHAN RUMPUT LAUT EUCHEUMA COTTONII

- VORLESUNG EINFÜHRUNG IN DIE GESCHICHTE DER LATEINAMERIKANISCHEN LITERATUREN UND

- PRACTICE QUESTIONS FOR GENERAL INTERVIEWS PERSONAL QUALITIES PLEASE

- EL MONCHO Y MATE COCIDO POR SUERTE LLEGÓ TARDE

- CRNA GORA ZAVOD ZA STATISTIKU S A O P

- DILWORTH PEDIATRICS PEDIATRIC DOSING GUIDE BY WEIGHT PROBLEM MEDICATION

- KENDİNDEN YÜRÜYÜŞLÜ MAKASLI PLATFORM KULLANIM KILAVUZU HD320L12 ORTAKONAK MAH

- ODDELEK ZA KMETIJSKO SVETOVANJE TRNOVELJSKA CESTA 1 3000

- TEMPLATE FOR CLINICAL RESEARCH ARTICLE 2 TEMPLATE FOR CLINICAL

- REPUBLIKA HRVATSKA ŽUPANIJSKI SUD U SLAVONSKOM BRODU URED PREDSJEDNIKA

- LIEVE LEON IGNACE DE NIL FINANCIAL REPORTING METHODOLOGY DEXIA

- JESSICA L COLEMAN JCOLEMANUTTYLEREDU OFFICE DEPARTMENT OF BIOLOGY UNIVERSITY

- FILOZOFSKI PROBLEM V ROMANU FRANCOSKI TESTAMENT PRIČNIMO PRIČUJOČE RAZMIŠLJANJE

- OTLEY 10 MILE ROAD RACE WEDNESDAY 10 JUNE 2009

- BAREVNÁ METEOROLOGICKÁ STANICE JVD DIGITÁLNÍ FOTORÁMEČEK MODEL JVD RB

414508DOC PAGE 1 OF 1 LABORATORY REPORT PREPARING A

414508DOC PAGE 1 OF 1 LABORATORY REPORT PREPARING A FIRST SCHEDULE FORMS [FORM A] APPLICATION FORM FOR GRANT

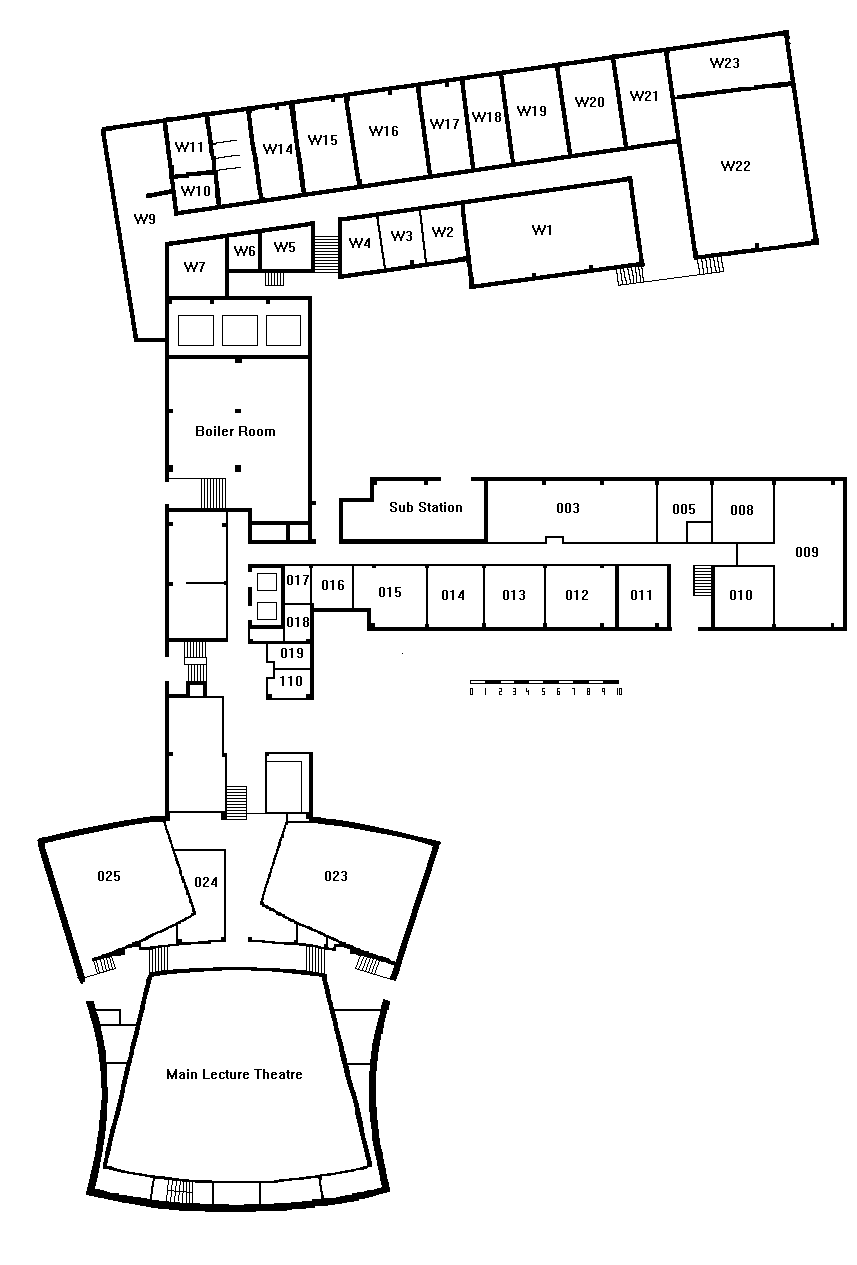

FIRST SCHEDULE FORMS [FORM A] APPLICATION FORM FOR GRANT ABERYSTWYTH UNIVERSITY HS&E OFFICE SAFETY MANAGEMENT BUILDING FIRE SAFETY

ABERYSTWYTH UNIVERSITY HS&E OFFICE SAFETY MANAGEMENT BUILDING FIRE SAFETYTEKNOLOGIHISTORIE – EMNET ATOMENERGI & ATOMBOMBEN ANSVAR OG TEKNOLOGI

Pisňi v Česť Presvjatoj Bohorodicy o Marije Mati

UNIVERSIDAD TÉCNICA DE ORURO FACULTAD DE DERECHO CIENCIAS POLÍTICAS

OYUN GRUPLARI İÇİN YEDEK PARÇA SATIN ALINACAKTIR GAZİANTEP BÜYÜKŞEHİR

NA TEMELJU ČLANKA 30 STAVKA 7 I ČLANKA 31

SPECYFIKACJA PRZEDSIĘBIORSTWO WODOCIĄGÓW I KANALIZACJI SP Z OO UL

RETIREMENT VILLAGE RESIDENT(S) SUBMISSION TO THE DIRECTOR OF CONSUMER

CAPITAL BUDGETING TECHNIQUES REQUIREMENTS CALCULATE THE PAYBACK PERIOD NET

CAPITAL BUDGETING TECHNIQUES REQUIREMENTS CALCULATE THE PAYBACK PERIOD NETEN COLOR LILA LAS QUE HE MEDIDO ? IMÁGENES

TERMÍNY VYSTOUPENÍ 842006 VIDČE 1500 HODIN 942006 ŠTUDLOV 1500

TERMÍNY VYSTOUPENÍ 842006 VIDČE 1500 HODIN 942006 ŠTUDLOV 15001 THE ELECTRONIC CONTROL DEVICE OF SMALLLIGHT MOPED 1

A1 ADD A KEZED H7 E A E

PROIECT ROMÂNIA JUDEŢUL MUREŞ CONSILIUL JUDEŢEAN HOTĂRÂREA NR DIN

PROIECT ROMÂNIA JUDEŢUL MUREŞ CONSILIUL JUDEŢEAN HOTĂRÂREA NR DIN8 WYBRANE SPOSOBY ROZWIJANIA MYŚLENIA TWÓRCZEGO W EDUKACJI

DANGEROUS GOODS CHECKLIST ITEM YES NO ACTION TO

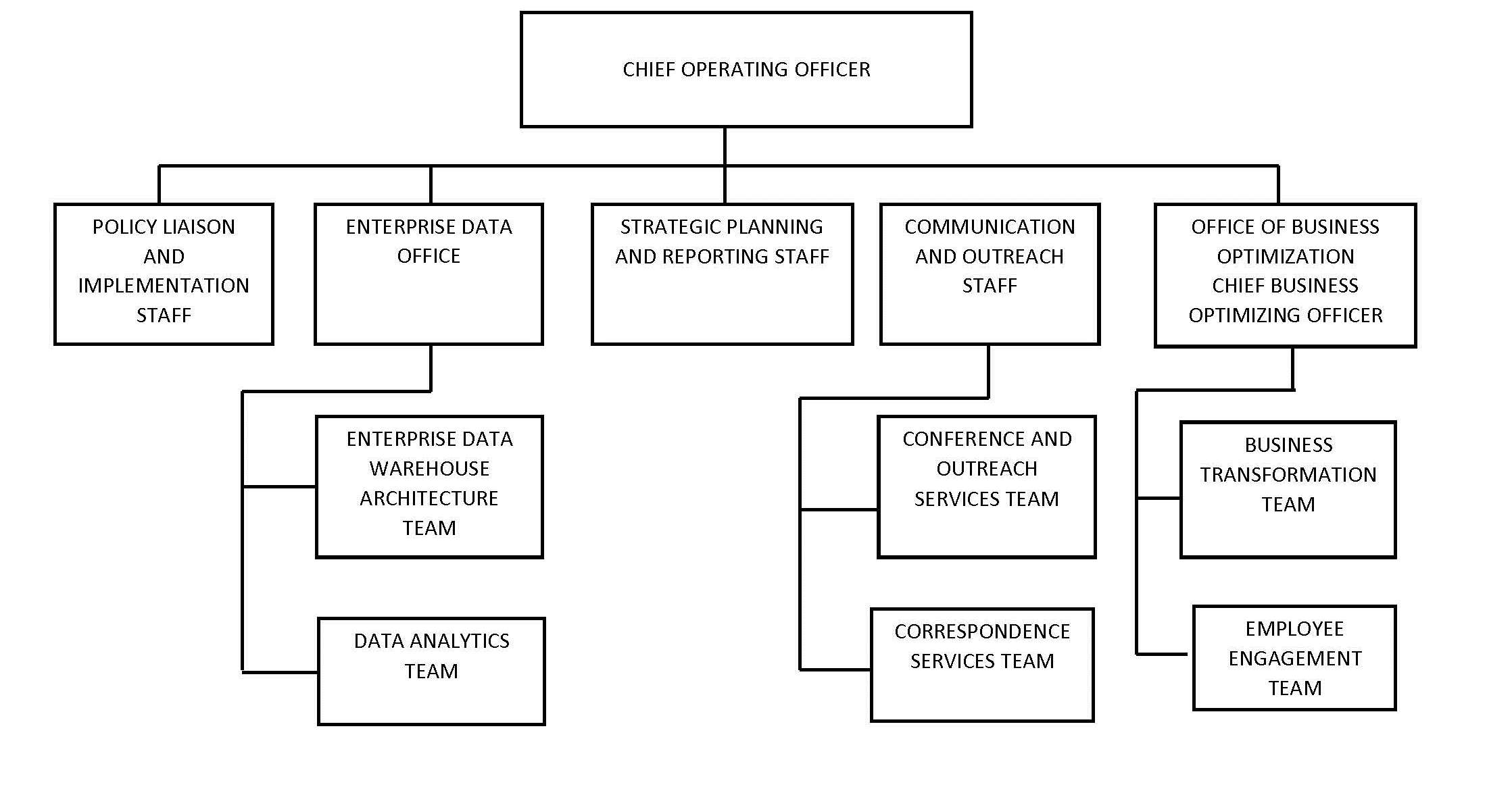

ORGANIZATION CHART – CHIEF OPERATING OFFICER

ORGANIZATION CHART – CHIEF OPERATING OFFICER AIR QUALITY MONTHLY HAZARDOUS MATERIAL USE FUEL CONSUMPTION AND